Gourmondo’s goal is to bring joy to your life. Everyday, the catering company delivers a thousand boxed lunches to workplaces across the Seattle metro, bringing breakfast spreads to baby showers and wowing wedding guests with unforgettable finger foods.

But if you ask founder and CEO Alissa Leinonen, the last few months — or even the last five years — have had about as much levity as a funeral procession.

“You're seeing so many fabulous businesses closing right now in our space,” she said, and she’s not wrong. You don’t have to look very far to find establishments with decades under their belt going belly up.

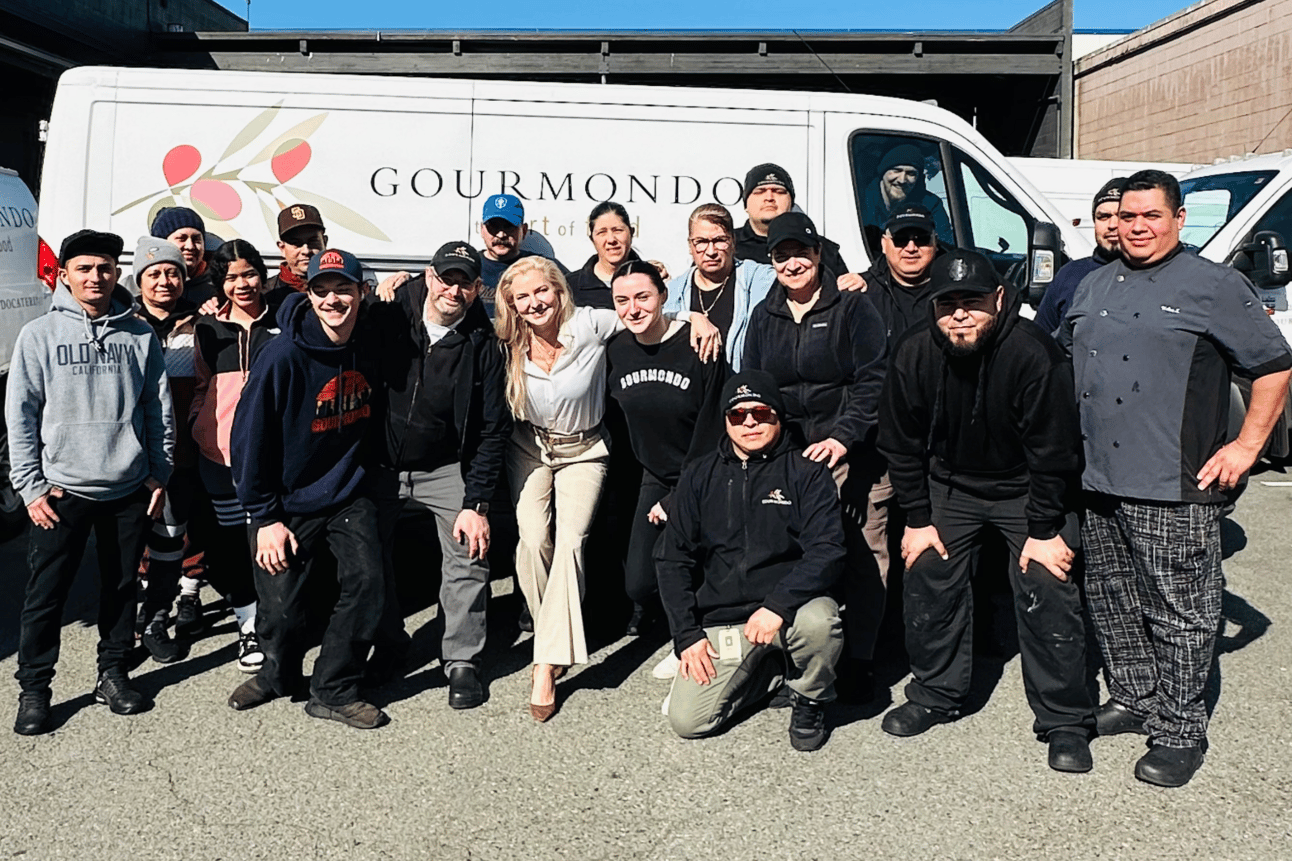

Gourmondo first opened in 1996 in the back of Pike Place Market. Today, the talented team of chefs and bakers create enticing spreads like this one. Photo courtesy of Gourmondo

In a post-pandemic world, recovery is certainly not the word on anybody’s lips. “Just out of COVID, you were pretty lucky if you could break even,” Leinonen said. “ And now, we're in an environment where even if you are optimizing all your expenses, you're looking at a negative seven to ten percent loss. It's just simple math.”

Rising labor costs are hitting hard in Gourmondo’s kitchen and at its two grab-and-go cafes (Cafe Omeros and Cafe MOHAI). At the end of last year, Seattle City Council pushed through what many restaurateurs saw as a hasty and harmful minimum wage increase to $20.76 per hour. Where before, small employers could count employees’ tips and/or medical benefits toward minimum compensation requirements, that’s no longer an option. It’s now a uniform rate across the board — $4.10 higher than the state minimum wage.

Leinonen feels like her and other’s concerns are not being taken seriously by local politicians. “They said, we've done our analysis. We fully expect 30% of your industry not to make it next year and that is a price we're willing to pay,” she said. “Wow. It's just gut wrenching. We put our heart and soul into our businesses. We're not driving around Porsches. We're really just trying to do what we love and serve our community.”

For employees, the change is a double-sided coin. On the one hand, inflation and the cost of living continues to skyrocket, so any boost helps — and Leinonen understands this fact. “We love our employees. They really are an extension of your family. They really are your utmost priority and they are the magic of your business.”

Alissa Leinonen (center) said “I think there are so many ways that we can work together. It's worth looking at different tax incentives or advantages for employers as they are investing in their employees. Where can we take off some of the pressure points?”

But it can cause resentment within the workplace too. Take a newly hired dishwasher, for example, who is already making as much as a line cook who’s put in a few years of service.

“They want to feel like we're compensating them for the experience that they've been gaining and the work they've been doing,” she explained. “So it has a ripple effect, on a number of different stages and layers of labor.”

Then you think about the word that is at the top of everybody’s minds — tariffs. Like salt in a wound, the economic uncertainty is forcing cash flow decisions and squeezing already razor-thin margins.

“So much of our packaging is coming from overseas and a lot of what we do is grab-and-go. We started negotiating to purchase larger inventories of the products that we knew were vulnerable, like olive oil from Italy,” Leinonen said. ”We are in the business of nickels and dimes in food. So when the cost of Parmesan Reggiano goes up by 20 cents a pound, that's meaningful for us, because we might go through thousands of pounds of it every month. It's just so challenging to navigate. This is beyond a headwind.”

In meetings with other hospitality CEOs, Leinonen has had tough conversations about how to keep their doors open amid this adversity. “You have two choices — you increase prices or you wrap up,” she said. “You’re seeing people's appetites both literally and figuratively start to lessen, and as a result of that, we start to pull back our workforce because we don't need to produce as much when we're not selling as much.”

It’s a vicious cycle that tends to paint business owners as the bad guys, which Leinonen insists is just not the case. To change this perception and the reality, she appeals to better, and more nuanced support from policy makers. “With small- and medium-sized businesses, there are five times more of us than there are at Amazon, right?” she asked. “There's got to be a way to reset and create a more supportive and collaborative partnership with the city, because we love our communities.”